- April 12, 2019

- Parisian theatre

- Anna Livesey

He is widely considered the founding father of French tragedy but many outside of France will never have heard of Pierre Corneille. Penning a whopping total of 32 plays in 55 years, this prolific 17th century writer was among the finest of his era, trumped in notoriety only by Molière and Racine. Corneille’s penchant for classical tragedy earned him his nickname, French Sophocles, and also triggered a literary furore that would change the course of his country’s theatrical history. Here’s all you need to know about this lesser-known giant of the early French stage…

Modest beginnings

Born in Rouen to a well-off but not wealthy, middle rather than upper class family of lawyers, there was little in Corneille’s background to hint at the illustrious prospects ahead of him. Having completed his studies with flying colours, the young Frenchman followed in the footsteps of his father, uncle, and grandfather before him, becoming a lawyer. But throughout a mediocre legal career that, ultimately, lasted many years, Corneille’s real love for literature was never far from the background. In 1969, at the ripe age of 23, the budding playwright put aside his lawyer’s garb and turned his talents momentarily to writing.

This was the year that, much to his own surprise, Corneille’s first comedy was accepted by a travelling theatre troupe. The witty dialogue and subtle parody of Mélite, reputedly inspired by its young author’s own early misadventures in love, were worlds apart from the cruder farces that dominated comedy of the time. The play proved a roaring success with audiences in Paris and, on the back of this break-through, Corneille began to write regularly.

Richelieu's Five Authors

A sparkling career takes off

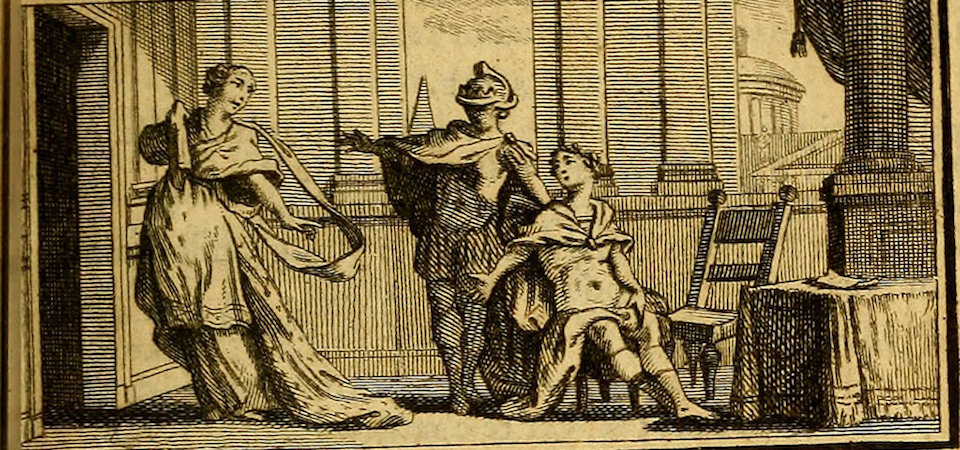

Fired up by this success, Corneille moved to the capital that same year and quickly became one of the French stage’s leading playwrights. His work caught the attention of the Cardinal de Richelieu, a powerful clergyman, statesman, and patron of the arts, who invited Corneille to join a group he called ‘The Five Authors’. In return for his patronage (the easiest and virtually only way to make big bucks from writing back in the day), Richelieu commissioned Corneille and four other influential writers to craft a series of plays inspired by ideas of his own. But Corneille soon tired of this collaborative project, frustrated by the restrictiveness of the Cardinal’s vision and infuriating the latter by deviating from its parameters. Tensions mounting, the playwright returned to Rouen.

A Controversial Masterpiece

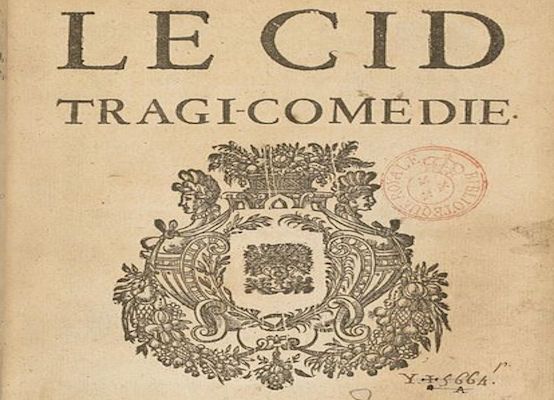

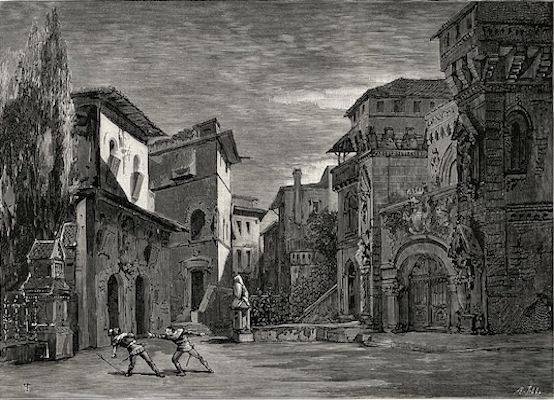

It was in the years following his break with Richelieu that Corneille penned the work now considered his masterpiece. With a plot that derives from popular Spanish legend, The Cid is a tragic tale of love and revenge. Starcrossed lovers Chimène and Rodrigue are caught in the web of their families’ feud: despite the pair’s passionate loyalty to one another, their medieval society compels them to honour blood ties above all others. This unspoken duty draws the two lovers into a spiral of vengeance from which only their love can lift them. The Cid is widely acknowledged to be among the most significant works in the history of French drama.

Interested in classics like the ones Pierre Corneille wrote? The Theatre le Ranelagh is known for producing timeless French plays. Check out what’s on for them in the future! Shows at Théâtre le Ranelagh.

The Institut de France, home to the Académie française

The Qarrel of The Cid

The Cid was an instant success upon its publication in 1637. Contemporary audiences were delighted by the hairpin plot twists of the play and its groundbreaking blend of comic and tragic genres. But these very attributes also sparked a heated controversy, in which Corneille’s work was ravaged for its violation of classical convention. A vicious pamphlet war now known as ‘The Quarrel of The Cid’ saw rival playwrights taking to the pen to attack Corneille and his play, with the latter responding by handing out personal insults left, right, and centre. The dispute came to a head when Cardinal Richelieu’s newly founded Académie française ruled that, though beautiful, The Cid broke too many of Aristotle’s principles to be either plausible or of literary value. His ego badly bruised, Corneille retreated once again to Rouen. It would be three years before he mustered up the courage to produce another play.

Corneille toes the literary line in later life

But, unable to resist the pull of the stage, Corneille did make a come-back after this three year hiatus. Across the 1640s, 50s, and 60s, the playwright published a whole host of more well-behaved tragedies and comedies (though none would achieve the cultural status of The Cid). Meanwhile, Corneille was busy pursuing his own familial duties as a devoted husband and father of seven children. In 1670, now 64, the playwright was asked to deliver a dramatisation of another classical story: that of Roman emperor Titus and his lover Berenice. Little did Corneille know that his efforts were to be pitted against those of a younger and up-and-coming playwright, Jean Racine, who had separately been issued exactly the same challenge. Racine’s Bérénice was widely found to be superior to its parallel by Corneille, Tite et Bérénice, heralding the older playwright’s gradual replacement by younger faces of the French theatrical scene.

Corneille in later life, Musée Pierre Corneille ©

Corneille’s Legacy

Corneille’s final play, Suréna was published in 1674, after which point the playwright retired from writing. He died ten years later in Paris and was buried in the graveyard of Église Saint-Roch, not far from Opéra. But Corneille's legacy was assured by a line of French playwrights who claimed him as their key influence. For Molière, Corneille was his master and the foremost of French dramatists, Racine told his son that the older playwright crafted verses “a hundred times more beautiful than his own”, and in his longest piece of literary criticism, Voltaire wrote that Corneille had done for the French language what Homer did for Greek. Or to put it in our words: Pierre was the original daddy of theatre in France.

Liked this article? Why not discover the lives of some other theatrical legends?