- June 24, 2025

- Theatre in Paris exclusives

- Eric Battye

What Barry Le Va and Samuel Beckett Can Teach Us About Theatre

Barry Le Va (1941-2021) was an American sculptor and installation artist. He is often described as a “process artist”, as his works rely on the process of their creation, playing on the many different possible outcomes of the same action. He explored this through actions like smashing glass, firing guns and dropping objects. His works were not, however, random mindless destruction: he drew detailed blueprints for each, outlining how each installation process should take place. Pictured below, his Cleaved Wall (1969/70) blueprints read: “12-14 cleavers running length of wall 23’, 5” from floor”, describing how the cleaver knives should be swung into the wall, and at what height.

As we can see from the image of the work’s 2024 installation at the Edinburgh Fruitmarket, the cleavers are stuck in the wall at varying heights and angles. It is impossible for the person constructing the sculpture to perfectly recreate a movement, to uniformly control the angle, speed and momentum they swing a knife into a wall, so even with the blueprints, no two installations of the work will be exactly the same. The variability of the process becomes the work itself: the audience is not simply looking at knives lodged in a wall; they are looking at different outcomes of the same experiment.

Le Va’s work provides an interesting framework for thinking about theatre. Like Le Va’s blueprints, play scripts rely on others to bring them to life. The way these instructions are carried out are endlessly variable, affecting how the play - like a knife into a wall - lodges itself in the audience’s imagination. Whilst a script tells an actor what to say, it does not tell them how to say it. The same line, read with different emphasis, intonation, timing and gestures can result in a completely different meaning - for example, “let’s eat grandma” is much less sinister than “let’s eat grandma”.

Similarly, there is the visual dimension to consider. Most scripts offer vague guidance on setting, costume, or the appearance of characters, leaving a director’s staging choices to dramatically shape the play’s tone. A woman of colour, for instance, playing a role traditionally assigned to a white man may provoke questions about race and gender that the original text does not explicitly address. Most playwrights appear not to object to such variability in the interpretation and performance of their scripts.

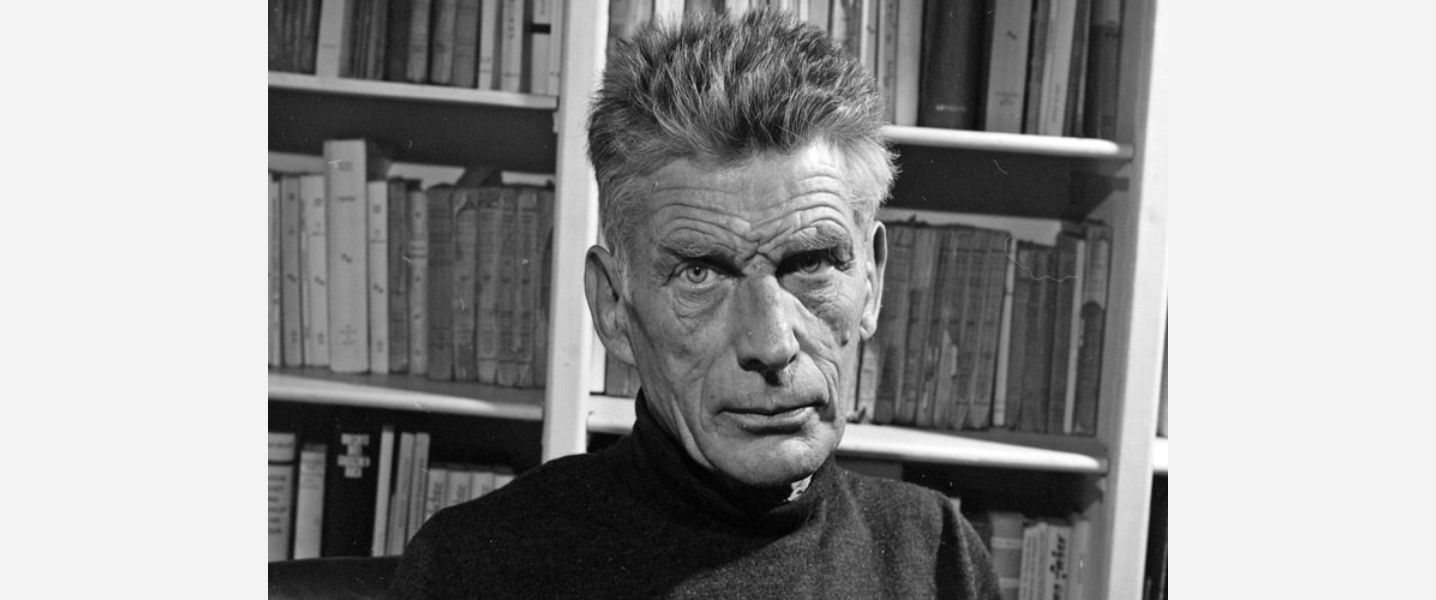

Irish playwright (and longtime Paris resident!) Samuel Beckett (1906–1989), however, was notoriously protective of his works.

This took many different forms, from meticulous stage directions in Footfalls (1975) - “Pacing: starting with right foot (r) from right (R) to left (L), with left foot (l) from L to R. Turn: rightabout at L, leftabout at R. Steps: clearly audible rhythmic pad. Lighting: dim, strongest at floor level, less on body, least on head.” - to sharply worded letters to directors, such as one to Roger Blin in 1957 - “One thing which annoys me is Estragon's trousers. [...] they were held up halfway [...] let the pants fall completely to his ankles. That must seem stupid to you but for me it is capital.”

Beckett’s strict control was not mere fastidiousness, rather a reflection of his minimalist aesthetic: every movement, pause and lighting cue was added for a reason, and so had to be executed precisely to preserve the emotional weight of his work without adding unnecessary details. He took this commitment so seriously that he - and later, his estate - did not hesitate to take legal action against productions that strayed from the script. For example, in 1988, he sued the Dutch theatre company De Haarlemse Toneelschuur for staging Waiting for Godot with an all-female cast. He argued that the play was written specifically for male characters, and that casting women imposed questions of gender that the original text did not intend to raise.

Barry Le Va’s intention was for his work to be - as suggested by the title of his posthumous 2024 exhibition at the Edinburgh Fruitmarket - In a State of Flux; the variability in how his work is carried out is the work’s very point. For Beckett, however, it’s the opposite: precision and invariability are the essence of his work. He is not just controlling the height at which the cleavers are swung: he is controlling the momentum, speed and angle they are swung with; he even controls who is allowed to swing it. So, whilst his aversion to reinterpretation may seem overly rigid – or even absurd – it reflects a fundamentally different artistic aim.

This raises a larger question: how much should a playwright’s intentions matter in a performance?

Would Chekhov approve of Elsa Granat’s Une Mouette, which reframes his 1896 play in a more psychological light?

Would Molière embrace Valérie Lesort and Christian Hecq’s addition of Balkan music and dance to The Bourgeois Gentleman?

Would Puccini understand why Claus Guth staged La Bohème in outer space, astronaut suits and all—or would he have preferred it remain in 1830s Paris?

And does it even matter? Does reinterpretation breathe new life and perspective into a play, or does it simply muddy the message?

It’s up to you. At Theatre in Paris, we’re both Beckett and Le Va: we love the originals, and we love their reworks.

THERE’S MORE WHERE THAT CAME FROM...

Whether you're a theatre aficionado or a first-timer, the Theatre in Paris newsletter has got what you need! At least once a month, receive a hand-crafted email for your browsing pleasure, listing the best exclusive updates, deals, programmes, and all things theatre.

You can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Pinterest, and TikTok by clicking the link below to see our Link in Bio page.